Megalis

General Information about Megalis

In conclusion, Megalis is a groundbreaking treatment for managing all symptoms of erectile dysfunction. Its efficiency, longer period of action, and effectiveness in improving total sexual satisfaction set it aside from different erectile dysfunction medicines. Its decrease danger of unwanted aspect effects and availability in different strengths make it a safe and personalised option for people experiencing erectile dysfunction. However, it is crucial to consult with a well being care provider earlier than starting any new medicine.

Megalis is also thought of a safer option in comparison with different erectile dysfunction medicines. It has a decrease danger of unwanted side effects similar to headache, flushing, dizziness, and nasal congestion. As with any medication, it is necessary to consult with a well being care provider before taking Megalis, especially in case you have underlying health circumstances or are taking any other medications. Your physician will be ready to advise you on the correct dosage and potential interactions.

Erectile dysfunction is a standard situation that affects millions of males worldwide. It is defined as the inability to achieve or keep an erection adequate for sexual exercise. While there are various remedies available, many of them include their own set of unwanted side effects or will not be effective for all individuals. However, there is a new revolutionary erection capsule from Switzerland that's gaining consideration for its effectiveness in managing all signs of erectile dysfunction - Megalis.

Another good thing about Megalis is its efficacy in managing varied symptoms of erectile dysfunction. It not solely helps with attaining and maintaining an erection, but it also improves overall sexual satisfaction. Many customers have reported experiencing elevated need, improved orgasms, and heightened pleasure while taking Megalis. It also has a optimistic impact on the psychological aspect of erectile dysfunction by boosting confidence and decreasing performance anxiety.

Megalis is a prescription treatment that's particularly designed to deal with erectile dysfunction. It is manufactured by Swiss pharmaceutical company, BiomPharm, and has been accredited by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The energetic ingredient in Megalis is Tadalafil, which belongs to a category of medicine often known as PDE5 inhibitors. It works by rising blood move to the penis, permitting for a firm and lasting erection.

One of the main benefits of Megalis over different erectile dysfunction medicines is its efficiency. While other drugs could need to be taken an hour before sexual activity, Megalis may be taken as little as quarter-hour prior, making it extra convenient for spontaneous sexual experiences. Additionally, Megalis has an extended duration of action with effects lasting as much as 36 hours, giving the consumer extra flexibility and less stress to carry out within a selected time-frame.

Furthermore, Megalis is on the market in varied strengths, permitting for a personalised therapy plan based on individual wants and preferences. The recommended starting dose is 10mg, however it can be adjusted to 20mg or 5mg depending on the person's response and tolerance. It is essential to note that Megalis ought to only be taken as soon as a day and never exceed the prescribed dosage.

Temperamental factors erectile dysfunction exercise order megalis 20 mg overnight delivery, such as shyness or behavioral inhibition, which also have a genetic component, also play a role. Although there are clear genetic underpinnings, developmental and psychosocial vulnerabilities, as well as acute and chronic stressors, contribute to their genesis and presentation. Functional imaging studies have shown decreased activity in the right orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex and increased activity in the amygdala, which is linked to fear responses. Although medications that prevent the reuptake of serotonin, thereby increasing serotonin levels, have been correlated with a reduction in anxiety symptoms, the exact mechanism of this is unclear. There have also been changes to the diagnostic criteria for agoraphobia, specific phobia, and social anxiety disorder, along with changes in symptom duration requirements. The child may become socially withdrawn, exhibit sadness, or have difficulty concentrating on work or play. Children with separation anxiety disorder tend to restrict social experiences away from home or attachment figures, and there is often excessive worry of potential harm, such as illness, injury, disasters, or death, to the attachment figure. The child may also experience excessive worry about getting lost or being kidnapped, if separated from his or her attachment figure. Additional problems triggered by separation or fear of separation may include sleep disturbances (eg, refusal to sleep alone), repeated nightmares, and somatic symptoms (which may include headaches, stomachaches, nausea, and/or vomiting). The symptoms last longer than 1 month, and their onset is generally before 5 years of age. The child may speak at home or with immediate family members but may not verbally respond to others when spoken to . The failure to speak is not due to any underlying expressive language deficit, and the child does not have any speech disturbances. Selective mutism results in impairment of social communication, occupational, and academic achievement. Exposure to the phobic object or situation consistently results in immediate fear or anxiety, which may be manifested in crying, tantrums, freezing, or clinging behaviors. For a diagnosis, a specific phobia must last for at least 6 months and result in functional impairment in home, work, school, or social interactions. There are International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for specific phobias. The child or adolescent avoids social situations due to fears that he or she may be negatively evaluated or may be embarrassed. A panic attack is a sudden intense fear or discomfort that reaches a peak within minutes. The panic attacks appear to occur without an obvious trigger, although most people identify a stressor several months before their first panic attack. The child or adolescent may go from a calm state to an anxious state and experience heightened autonomic nervous system symptoms, such as accelerated heart rate, sweating, shaking, shortness of breath, chest pain or discomfort, abdominal distress, numbness or tingling, and/or have a fear of dying or losing control. To meet criteria for panic disorder, a child or adolescent must have persistent concern or worry about additional panic attacks, and this worry must last greater than 1 month in duration. Many children who present with panic attacks will undergo lengthy and costly medical investigations. Children or adolescents with agoraphobia often have thoughts that something terrible might happen in the above situations. They may avoid situations or insist on the presence of a companion due to perceived difficulty escaping or being unable to find help in the event of incapacitating or embarrassing symptoms. These children or adolescents usually find it difficult to control their worries and have concerns related to their competence or quality of their performance, and whether or not others are evaluating them. They exhibit at least 3 symptoms that include feeling on edge, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance. Functional impairment is often secondary to the associated symptoms and the considerable time spent worrying. Obsessions and compulsions may be related to themes of contamination, symmetry, and fear of harm to oneself and others. Children aged 6 years or younger may not experience the traumatic event themselves but may witness it. Symptoms include: (1) intrusion symptoms, such as re-experiencing recurrent and distressing memories and dreams, dissociative reactions, intense psychological distress, and/or marked physiological reactions; (2) persistent avoidance of associated stimuli; (3) negative alterations in cognition and mood associated with the traumatic event or feelings of detachment; and (4) marked alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event. Anxiety Screening Tools Structured and semistructured diagnostic interviews, self-report rating scales, and clinician-rated instruments are the most common methods for identifying and measuring anxiety in the pediatric population. Ideally, information should be obtained from multiple informants, including parents and teachers. Younger children should be screened with parent report measures or interviewed with the use of visual aids, such as a feeling or mood thermometer. If the screening measures are positive for anxiety symptoms, the primary pediatric health care professional should determine which anxiety disorder might be present, the severity, and the degree of functional impairment. Specific phobias and dissociative disorders have also been known to occur in response to a traumatic event. Finally, any neurological damage that may have occurred due to the traumatic event should be assessed. Treatment Due to the shortage of mental/behavioral health professionals in almost all communities, primary pediatric health care professionals often need to become involved with the treatment and ongoing symptom reassessment of children with anxiety disorders. In follow-up studies of children who received treatment for their anxiety disorders, there was a decreased risk of developing another mental health disorder after 3 to 4 years. Measures overall anxiety levels and academic stress, test anxiety, peer and family conflicts, and drug problems.

Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents erectile dysfunction medication covered by insurance purchase discount megalis. Developments in pediatric psychopharmacology: focus on stimulants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics. Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. A systematic review of medical treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders. Risperidone for the core symptom domains of autism: results from the study by the Autism Network of the of the Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology. Efficacy of low-dose buspirone for restricted and repetitive behavior in young children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized trial. Pediatric prescribing practices for clonidine and other pharmacologic agents for children with sleep disturbance. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of controlled release melatonin treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome and impaired sleep maintenance in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Melatonin for sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: randomised double masked placebo controlled trial. They also have some questions about the value of certain vitamins and other supplements. Justin is in a well-designed preschool program and is receiving intensive applied behavior analysis services. Primary pediatric health care professionals and caregivers should consider several important questions when evaluating the merits of a particular treatment that is being promoted for children with developmental-behavioral disorders. What is the scientific rationale and evidence regarding the use of these therapies individually or in combination for children with developmental-behavioral concerns Is it plausible that these approaches should be expected to have efficacy in improving the symptoms of a developmental-behavioral disorder based on what we already know about neuroscience and how the body works How does one balance the desire of a parent to pursue a particular treatment with the right of a child not to be subjected to unsubstantiated therapies that may be ineffective or even harmful And importantly, how do we help caregivers learn the skills they need to critically evaluate the large number of remedies popularized on the Internet and social media Complementary and alternative medicine has been defined as "a broad domain of healing resources that encompasses all health systems, modalities, and practices and their accompanying theories and beliefs, other than those intrinsic to the politically dominant health systems of a particular society or culture in a given historical period,"1 and as practices "not presently considered an integral part of conventional medicine. Natural products include botanical agents, vitamins, minerals, and special diets, whereas mind-body practices include such approaches as massage therapy, yoga, chiropractic, and acupuncture. These questions can be grouped into 3 main categories that pertain to the theoretical basis of the therapy, the evidence base of the therapy, and the tactics used to promote the therapy (Table 24. Twelve Questions to Ask About a Complementary or Alternative Therapies(41,42) Questions related to the underlying theoretical basis for the therapy 1. Do proponents of the treatment cherry-pick data that support the value of the treatment, while ignoring contradictory evidence Do proponents of the treatment assume a treatment is effective until there is sufficient evidence to the contrary Do proponents claim that a particular treatment cannot be studied in isolation but only in combination with a package of other interventions or practices Do proponents of the treatment use scientific-sounding but nonsensical terminology to describe the treatment Evaluating the Theoretical Basis of a Therapy Therapies considered complementary and alternative have diverse origins and arise from a variety of theoretical frameworks. The following questions can help identify therapies that have a weak theoretical foundation: 1. Is the treatment based on proposed forces or principles that are inconsistent with accumulated knowledge from other scientific disciplines Many of the nonstandard therapies used in children with developmental-behavioral disorders are based on hypotheses that do not account for much of what we already know about the neurobiology of these disorders. While environmental factors that modify disease expression certainly should be explored even in disorders that have a strong genetic basis, therapies (eg, chelation therapy) based in a belief about the role of some environmental trigger are unjustified in the absence of good evidence that the particular environmental factor is actually etiologically related to the disorder. There should also not be a blind leap to link associated medical issues to the etiology of a particular developmental-behavioral disorder. One should look no further than trisomy 21 to find a disorder in which various gastrointestinal and immune abnormalities are common but not related in a cause-effect manner to the fundamental neurodevelopmental issues. Certain complementary health approaches also appear to be quite disconnected from what we already understand about how the natural world works. Therapeutic touch, for example, is based on the belief that an energy "biofield" exists in proximity to the human body and that imbalances in this energy field are responsible for human disease (including developmental disturbances). Practitioners of therapeutic touch believe that this energy field can be manipulated manually and can result in objective improvements in some aspect of physical functioning. This theory is fundamentally inconsistent with much of the accumulated knowledge in biology and physics. While people may certainly experience subjective improvement in some symptom after undergoing therapeutic touch, the mechanism for this improvement is likely based in placebo effects and not in the adjustment of "energy" imbalances. Another energy-based practice, acupuncture, also illustrates the principle that therapies remaining unchanged for many years (or centuries) may not be undergoing the error correction that is a necessary element of scientific practices. The appropriateness of considering plausibility in determining which novel therapies are worthy of formal investigation is especially relevant when research resources are limited. Several questions can shed light on whether there is an adequate evidence base to support the use of a specific therapy. Have well-designed studies of the treatment been published in the peer-reviewed medical literature

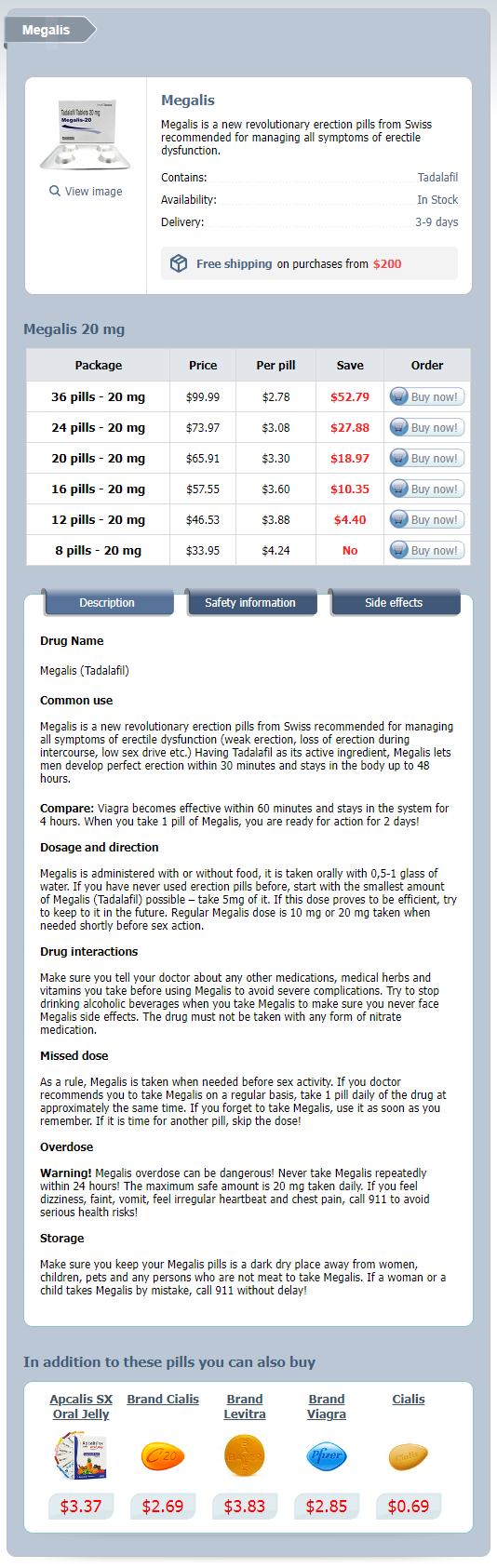

Megalis Dosage and Price

Megalis 20 mg

- 36 pills - $99.99

- 24 pills - $73.97

- 20 pills - $65.91

- 16 pills - $57.55

- 12 pills - $46.53

- 8 pills - $33.95

The test is positive when pain erectile dysfunction caused by nervousness purchase 20 mg megalis with visa, located to the subacromial space or anterior edge of acromion, is elicited by this manoeuvre. The examiner then stabilizes the upper arm with one hand while using the other hand to internally rotate the arm fully. The elbow is extended and the thumb points to the floor in full internal rotation. The patient is then asked to hold this position with downward pressure by the examiner. For partial tears of the cuff, more subtle tests are used to identify weakness in isolated components of the cuff. The patient (seated or standing) is asked to raise his or her arms to a position of 90 degrees abduction, 30 degrees of forward flexion and internal rotation (thumbs pointing to the floor, as if emptying an imaginary can). The examiner stands behind the patient and applies downward pressure on both arms, with the patient resisting this force. The result is positive when the affected side is weaker than the unaffected side, suggesting a tear of the supraspinatus tendon. Infraspinatus resisted external rotation the patient stands holding his or her arms close to the body and the elbows flexed to 90 degrees. He or she is instructed to externally rotate both arms while the examiner applies resistance; lack of power on one side signifies weakness of infraspinatus. The test can be repeated, this time with the arm in 90 degrees of forward elevation in the plane of the scapula. The patient is asked to laterally rotate the arm against resistance; the ability to do so despite feeling pain can indicate tendinitis while an inability to resist at all suggests a tear of infraspinatus. Subscapularis belly press test the patient is asked to place their hand on their abdomen and bring the elbow forward. If the subscapularis is torn, the patient will be unable to do this and the elbow will move backwards. This is seen in patients with tears of the infraspinatus and posterior part of the rotator cuff. In chronic cases the caudal tilt view may show roughening or overgrowth of the anterior edge of the acromion, thinning of the acromion process and upward displacement of the humeral head. There is almost complete loss of the subacromial space, and osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint. Sometimes there is calcification of the supraspinatus, but this is usually coincidental and not the cause of pain. Healing is slow, and a hasty return to full activity may often precipitate further attacks of tendinitis. Provided the patient has a useful range of movement, adequate strength and well-controlled pain, non-operative measures are adequate. If symptoms do not subside after 3 months of conservative treatment, or if they recur persistently after each period of treatment, an operation should be considered. Certainly this is preferable to prolonged and repeated treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs and local corticosteroids. The indication is more pressing if there are signs of a partial rotator cuff tear and in particular if there is good clinical evidence of a full-thickness tear in a younger patient. The latter is technically more demanding but it can produce results equivalent to those of open surgery. Physiotherapy, including rotator cuff exercises and scapular setting, may tide the patient over the painful healing phase. A short course of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory tablets sometimes brings relief. If all these methods fail, and before disability becomes marked, the patient should be given one or two injections of depot corticosteroid into the subacromial space. Through an anterior incision the deltoid muscle is split and the part arising from the anterior edge of the acromion is dissected free, exposing the coracoacromial ligament, the acromion and the acromioclavicular joint. The coracoacromial ligament is excised and the antero inferior portion of the acromion is removed by an undercutting osteotomy. If the joint is hypertrophic, the outer 1 cm of clavicle is removed; this last step exposes even more of the cuff and permits reconstruction of larger defects. An important step is careful reattachment of the deltoid to the acromion, if necessary by suturing through drill holes in the acromion; failure to obtain secure attachment may lead to postoperative pain and weakness. Other methods to reconstruct irreparable tears in the younger patient include supraspinatus advancement, latissimus dorsi transfer, rotator cuff transposition, fascia lata autograft and synthetic tendon graft. Acute rupture of the rotator cuff in patients over 70 years often becomes painless; although movement is restricted, operative repair in this age group is less reliable. The underside of the acromion (and, if necessary, the acromioclavicular joint) must be trimmed and the coracoacromial ligament divided or removed. If a cuff tear is encountered, then it may be possible to repair it; otherwise the edges can be debrided or an open repair undertaken. This procedure has now become the preferred treatment and allows earlier rehabilitation than open acromioplasty because detachment of the deltoid is not performed. Arthroscopy allows good visualization inside the glenohumeral joint and therefore the detection of other abnormalities which may cause pain (present in up to 30% of patients). It allows good visualization of both sides of the rotator cuff and the identification of partial and full-thickness tears. The arthroscopic instruments, suture anchors and knot tying techniques have quickly evolved to allow full arthroscopic repairs although most authors describe a steep learning curve.